Camac Blog

Business sponsorship for musicians

News

July 14, 2015

A wise person should have money in their head, but not in their heart.

Jonathan Swift

A modern woman must be assertive, like a man, when it comes to looking after her career trajectory. Mindful of this, a musicologist I know asked her sort-of employer (she was a paid-by-the-hour assistant in a conservatoire) if it would be possible to confirm the permanent contract she had been promised for the last seven years. He told her to “find a rich husband”. This actual response from a pillar of the musical establishment in 2016 has inspired me to discuss a more constructive and sustainable way of making art happen: business sponsorship for musicians.

Musicians have always had to spend time thinking about money. Be it via employment, fundraising, patronage, sponsorship, a scholarship or a grant, we invest in music to draw out riches that are not fiscal.Thus far, no-one’s asked to marry the Camac sponsorship department, but we certainly welcome good partnerships. Most important of all, of course, are the direct partnerships with the artists themselves. We have also contributed extensively to matching funding schemes, crowd funding schemes, and we try and keep up to speed with the latest possibilities.

To this end, I recently went to a conference about fundraising. It was run by Ashoka, who train “Changemakers”: people who respond imaginatively to problems, and drive effective change. A lot of these changemakers are social entrepreneurs: people who use their business activity to make a positive impact on society. This work model is closely comparable to what musicians have been doing for centuries.

You can define fundraising as the collection of necessary resources, which cannot be garnered from market activity. But while this is a one-way, or at least not immediately or wholly two-way street in financial terms, it is nonetheless a partnership. The word “fundraising” is rooted in solidarity: when the Pilgrim Fathers boarded the Mayflower in 1620, they promised to “fund each other”, to support each other on their great, unknown adventure. To this day, effective fundraising is a steady, gradual process, which relies as much on interpersonal relationships as it does on a chequebook.

There are many different types of funding. It might sometimes feel like the answer to your prayers would indeed be a rich spouse, but real fundraising offers all kinds of pairings. Creativity is rarely vague, and it is also important to be clear-minded about your options. Sponsorship, for example, involves the interests of the sponsor in one way or another, whereas a charitable donation may be entirely disinterested, even anonymous. Or it may not be: most foundations and grant-giving bodies have tight criteria governing who they may support. It’s important to consider what sort of funding will best fit your project. A wealth of concrete research exists to help you decide, from the German Bilanz des Helfens about what private donations are given by whom, to the advice and resources published by the British Arts Council.

It’s easy to get caught up in a rush of planning enthusiasm and want to go international straight away, but it is much more canny to start local, expand later. More local usually equals more closely relevant: you’ll get a better audience with a local focus, and local funding bodies are more likely to be interested in your project. It’s also wise to base as much of your investment, as well as what you get out of that investment, within one economy. It always works better, for all sorts of reasons. We instrument manufacturers always have local partners.

It’s easy to get caught up in a rush of planning enthusiasm and want to go international straight away, but it is much more canny to start local, expand later. More local usually equals more closely relevant: you’ll get a better audience with a local focus, and local funding bodies are more likely to be interested in your project. It’s also wise to base as much of your investment, as well as what you get out of that investment, within one economy. It always works better, for all sorts of reasons. We instrument manufacturers always have local partners.

Having found your funding match(es), at home or abroad, the partnership gets deeper. Above all, people sponsor people. Relationship fundraising (or “friendraising”, as it’s now sometimes called) was first defined by Ken Burnett in 1992, and posits the idea of genuine, individual and long-term friendships between doners and fundraisers. Statistically speaking, it is actually quite easy to get a project funded for the first time. The real work is done developing your relationships in the longer term.

Like most things, our own sponsorship always works best when it is built on solid foundations. In harp maker sponsorship, that means genuine enthusiasm for the maker’s harps on the part of the artist, and respect for artistic as well as commercial concerns on the manufacturer’s side. We can then have real dialogues with artists: about their projects, about our instruments. We take their suggestions for improvements on board, and we can discuss our own position honestly with them. We rejoice with them over their successes. “Our” artists do become our friends, and this is deeply rewarding, hugely satisfying.

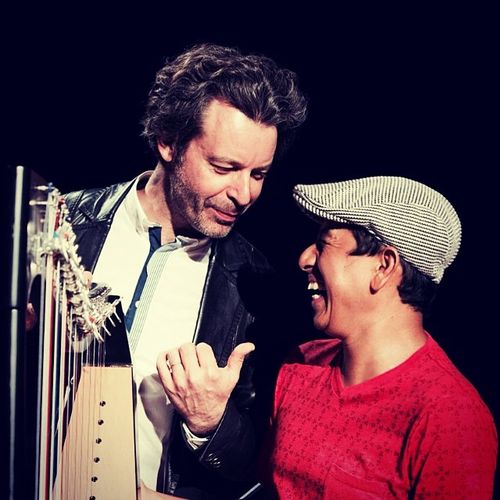

Jakez and Klaus Horngacher have some fun in Beijing

Less satisfying are complaints that we and harp firm B won’t work together, that the project would be so much easier to finance if we would all get over ourselves, for a good cause. As the bar at the World Harp Congress will show you, we enjoy a drink with our colleagues in other harp firms. But it is very rarely possible to co-sponsor with one’s direct competition. Not because we are toothy sharks, but because to do so would be stupid business practice. Good, not stupid business practice is what creates the means to fund good causes.

A good business is not grubbing at the base of the celestial ladder of morality. I have had interesting conversations with public institutions, who have refused to house events that their harp teachers want to run, because of the connection with our business. To give you an important counter-example from real life, the Vienna State Opera is sponsored by Lexus.

But is it a Lexus? #notthepoint

Do all the musicians in the Vienna Phil drive a Lexus? Do you see the opera as, in the first instance, an advertisement for Lexus? Even if Lexus wanted this – in reality, they are much too sensible – it wouldn’t work. Nobody, rightly, would appreciate thinking they were coming to experience a wonderful opera, and instead being sold a car. It is the same with any business sponsorship of the arts.

As a business, you have certain financial means at your disposal. If you want, you can put them to a good cause, enjoy some extra exposure, and derive great satisfaction for having done something fine with your money. That somebody is a businessman does not mean he has no values. Nor does it mean that his concerns aren’t important or valuable. A business relationship, like any other relationship, is a two-way process, best working with integrity, trust and mutual respect.

Consider your sponsor’s interests: what they want to ensure, what they have to ensure. Create something that is good for both you. Say thank-you (your sponsor will say the same to you), and once the project is over, don’t disappear. It isn’t greedy to come back and ask for more. Done well, it’s the next step in the partnership. Above all, start from what you genuinely believe in. In our world, that means: begin with the harps you love the most.

Edmar Castaneda, Jakez François