Camac Blog

World Premier of “Mercure” by Philippe Schœller

Latest

September 8, 2018

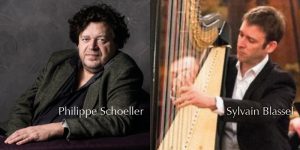

On September 8th at 18:30, as part of the Harfenfest Luzern, Sylvain Blassel will give the world premier of “Mercure” by Philippe Schœller. This is the fourth solo work for harp by the well-known French composer, following Esstal (2002), the as yet unpublished ‘Zeitgeist’ (2018), and a concerto – Hêlios (2001-2002). There is also a significant body of chamber music, including Visions de Nefertiti I for viola, alto flute and harp (2016); Hypnos linea for female voice, lever harp, flute, tambour and percussion); Aurore Australis and Borealis for mandolin, harp and guitar (2005); Incantation sixième for sextet and harp (2003); Isis II (2000-2001) and Volubilis (1995), both for bassoon and harp (2000 – 2001); and À l’aube où les sources for guitar, harp, two chromatic accordions, and viola da gamba. The list of works alone highlights a fascination with the classical / archaic, and in a great diversity of colours and combinations for the harp.

On September 8th at 18:30, as part of the Harfenfest Luzern, Sylvain Blassel will give the world premier of “Mercure” by Philippe Schœller. This is the fourth solo work for harp by the well-known French composer, following Esstal (2002), the as yet unpublished ‘Zeitgeist’ (2018), and a concerto – Hêlios (2001-2002). There is also a significant body of chamber music, including Visions de Nefertiti I for viola, alto flute and harp (2016); Hypnos linea for female voice, lever harp, flute, tambour and percussion); Aurore Australis and Borealis for mandolin, harp and guitar (2005); Incantation sixième for sextet and harp (2003); Isis II (2000-2001) and Volubilis (1995), both for bassoon and harp (2000 – 2001); and À l’aube où les sources for guitar, harp, two chromatic accordions, and viola da gamba. The list of works alone highlights a fascination with the classical / archaic, and in a great diversity of colours and combinations for the harp.

“The harp is a symbol of archaism”, Schœller explains. “Not archaic in the sense of being against modernity, but rather in reference to the earliest periods of culture. The harp is at the core of the history of musical instruments, at the birth of art. I have composed many works for harp in the course of the last fifty years, since I was very young. I love the harp, and in music, you don’t orientate yourself by what is true or false, but by what you like or don’t like. And if you are faithful to what you like, then you are classique. You are not modern in the sense that you seek to break away from something. You are seeking communion with with your own deep and real nature, with your world of concepts and thoughts. This is essential.

In fact, what people call modern music, or contemporary music, is in crisis because of this sort of rupture. Nobody thinks they will like it, there’s no audience for it. There isn’t a strong musical reason for this – put a well-written piece in front of an audience, and it will appreciate it regardless of the era. Moreover, children are particularly receptive to and enthusiastic about new music. But contemporary music has not entered into our mainstream culture, otherwise there would be more curiosity and enthusiasm for it in general.

I have never been interested in being a “composer of contemporary music.” I don’t want to feel divorced from history, or at odds with our times. Music is about harmony, be it from the Beatles or Guillaume de Machaut. It’s very difficult that contemporary music is isolated from all this, although it can be easier to listen to than Bach or Haydn. To look to the archaic is a natural response to this situation, and it’s something that I, as a musician-composer, like very much to do. I find the harp very touching because while it is highly modern in its double-action form, it remains an artisan instrument with a powerful archeology. The harp was part of ancient rites, played by antique visionaries, and you still produce the sound directly with your fingers or nails. There’s no mechanical interjection, as with the hammers on the piano. The harp is not at all industrial, in this sense.

I also love how the harp can be at once subtle and savage, delicate and archaic. It’s an instrument that sets its rules for a composer, with the pedals and so on, but it’s an instrument with real authority. You cannot ignore the sound of the harp. It has a grace, a finesse, a virtuosity in the playing of it, and a mystery which all capture the attention. Sometimes I imagine a table of politicians, where everybody is shouting to make themselves heard, and I feel that contemporary music has become like this. But the harp is not like this, because the free resonance of its strings ends in silence. It is as if the harp’s goal is to create silent space around it, and it is in the space of silence that music begins.”

‘Mercure’ is a piece that came to me very easily – like ‘Esstal’, one of my other pieces for solo harp, which was written very instinctively in the space of one day. There are pieces like this, which arise naturally from the sensibility one feels for the instrument. Sylvain Blassel asked me for a piece because he knew my concerto and also ‘Zeitgeist’, a piece I wrote for another harpist friend and which has not yet been published. ‘Mercure’ is also connected to another work of mine – Hermès V, which I wrote for the Ensemble Intercontemporain and particularly Mathias Pintscher, who I so admire. All my music works like this; I am constantly seeking to make connections and harmony, a sort of benevolence.

‘Mercure’ is a piece that came to me very easily – like ‘Esstal’, one of my other pieces for solo harp, which was written very instinctively in the space of one day. There are pieces like this, which arise naturally from the sensibility one feels for the instrument. Sylvain Blassel asked me for a piece because he knew my concerto and also ‘Zeitgeist’, a piece I wrote for another harpist friend and which has not yet been published. ‘Mercure’ is also connected to another work of mine – Hermès V, which I wrote for the Ensemble Intercontemporain and particularly Mathias Pintscher, who I so admire. All my music works like this; I am constantly seeking to make connections and harmony, a sort of benevolence.

Hermès V is a piece on the beauty of chaos. Chaos theory is about everything we don’t understand, and Hermès is an ambiguous god, a cunning trickster constantly on the move. Some people are afraid of the unknown, but I’m always interested in what is not known. Close alongside Hermès you have Mercury, both gods of messages, eloquence and of trade. For me, music is also about sharing and exchange, never splendid (or unsplendid) isolation. Mercury and Hermès also share particular aspects, for example winged shoes (talaria), and a staff with two interlaced serpents, Hermès’s gift from Apollo. Mercury often carries a tortoise, because he is said to have invented the lyre from a tortoise shell. Most importantly, Mercury is the planet closest to the sun. There is also a strong sense of something shining, shining out to the audience in this piece. More than anything, it is this sort of shining and expansive quality that I associate with the harp.”

“Philippe Schœller is not only a composer, but also a poet”, Sylvain Blassel continues. “My experience of his music intensified at the world premier of his harp concerto, Hêlios, which was given by Frédérique Cambreling and the Orchestre National de Lyon twenty years ago. I well remember the impression his strongly poetic discourse made on me, independent of the fact it was a harp concerto. The orchestration was very rich, with intensely varied and shimmering colours; the harp writing, which was in conflict as well as in resonance with the orchestra by turns, was also particularly successful. But above all, I found his aesthetic language to be quite unique, and completely authentic. Ever since then, this language has stayed just as teemingly vigorous.

I am delighted by ‘Mercure’, this new piece for harp – which is still really new, as it only saw the light of day a month ago! It is a distinctive work for Philippe. I don’t mean that he is taking a new aesthetic direction, but ‘Mercure’ seems to me to be almost like a reduction of an orchestral score, rather than solely a work for harp. I have decided to premier it in my recital otherwise entirely devoted to Liszt, because Liszt and Schœller share the same orchestral dimension: on the piano for the one, and on the harp for the other.

‘Mercure’ offers different types of musical “objects”, which go far beyond simple contrasts. Each element is clearly identifiable. But unlike a Wagnerian leitmotiv, each element has its own life, transformations, and developments. A long cantus firmus, in octaves, progresses implacably throughout the piece: solid, imperturbable and and almost ceremonial, echoing the grandeur of Mercury. Its shadow – but not its exact shadow – is seen in a passage with an inflexible ostinato on a single, slowly repeated note. Throughout the work, little, acrobatic arabesques seem to grown gradually more influenced by Mercury’s voice. They begin pianissimo, like a rumour, then get louder and louder in celebration of his power, ffff and thunderous.

There is no doubt that there is a narrative aspect to ‘Mercure’, and everybody can imagine the story unfolding. As well as the orchestral dimension, all the different elements in the piece are organised to bring out the effect of the harp’s registers, as they would be on the organ. This isn’t in order to bring out different timbres (in this regard, the harp writing is quite traditional – it is everything other than a succession of different playing techniques), but on the contrary, it juxtaposes different sonic plains, of which the effect is to increase the intelligibility and general transparency. As you would see in narrative emphasis, the discourse employs an unusual dramaturgy, which avoids traditional ideas of transition and development, in order to concentrate better on rhetorical techniques and processes.”