Camac Blog

‘The Dawn of the Celtic Harp’: Interview with Mariannig Larc’hantec

News

September 17, 2016

The Celtic harp is commonly seen as an ancient instrument. Heard casually, ‘Celtic’ suggests folklore, myth, harps carved in intricate lacework patterns, crystals, and so on. But in fact, nobody really knows what the harp was like in Celtic times. Little was written down, and in any case ‘Celtic’ involved a wide range of cultures. There is no such thing as any one “Celtic harp.”

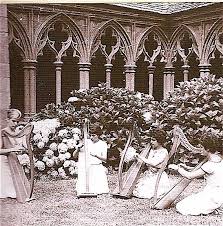

Telenn Bleimor, Denise Mégevand’s Paris-based ensemble of five Breton harps. Many of today’s well-known Breton harpists began their careers in Telenn Bleimor: Madeleine Buffandeau, Brigitte Géraud (Baronnet), Mariannig Larc’hantec, Kristen Noguès, Françoise Johannel, and Rozenn Guilcher, to name but a few.

The beginnings of renewed interest in Celtic culture were not primeval or folkloric either. They belonged in large part to the intelligentsia: like Romanticism, the Celtic revival was an intellectual movement. Middle-class Bretons in Paris, for example, were searching for an alternative identity to that of centralised France. It was the Breton-Parisian Théodore de la Villemarqué, researching oral Breton literature, who found the harp mentioned. He optimistically concluded that the harp had belonged to Ancient Breton bards; even to priests.

The Breton Celtic Revival was a period of enormous development for the lever harp. Our beginnings as a company are closely connected to this time, and we still make all our harps in the Breton ateliers we have always had. You can read a more detailed history of the lever harp in Brittany here.

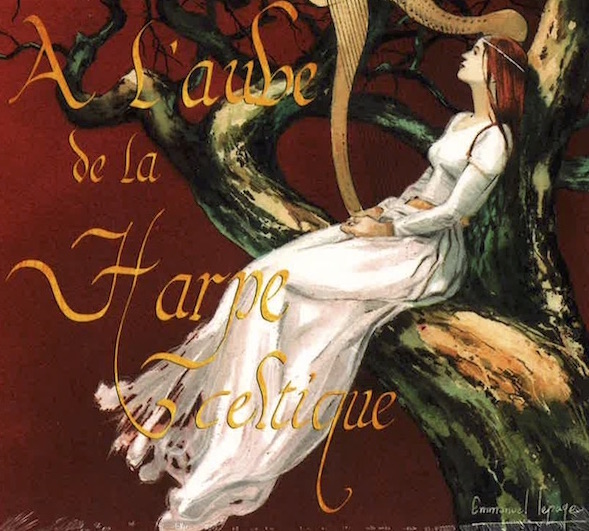

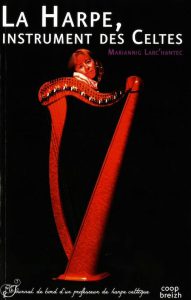

Two central figures for the lever harp in Brittany are Mariannig Larc’hantec, and François Pernel. Our e-store is currently featuring Mariannig Larc’hantec’s latest book La Harpe, Instrument des Celtes. Even more recently, she has released a CD: A l’Aube de la Harpe Celtique (‘The Dawn of the Celtic Harp’). This disc is the fruit of a collaboration with François Pernel – Mariannig has composed all the music, and François performs it.

Find out more in the following interview with Mariannig Larc’hantec!

How did you come to write ‘La Harpe, Instrument des Celtes’? Was it something you had had in mind for a long time?

I feel like I had an experience that, for want of being historic, was almost prehistoric. The Celtic harp only existed in the hands of some neo-druids, in other words it was germinating among some idealists. When it finally saw the light of day, it was the result of people searching for a cultural identity, plus the work of musicians and inventors. Once the first instruments had been produced by their creators, they sparked all sorts of questions. Some were as simple as “how shall we play this?”, and no sooner had one begun to grasp that, “what are we going to play”? These interrogations are at the heart of what is happening now. It so happens that I experienced this period. I also experienced at close hand lever harp teaching in its infancy, as it began to be undertaken in institutions. I was fortunate enough to discuss its potential and its future in the cultural landscape – Breton, first of all, thereafter French. The issue was the place of what was loosely termed “traditional music” in musical teaching centres. It was important to me to document these debates. Now, everything seems settled and established since – as my pupils sometimes say – the dawn of time.

I feel like I had an experience that, for want of being historic, was almost prehistoric. The Celtic harp only existed in the hands of some neo-druids, in other words it was germinating among some idealists. When it finally saw the light of day, it was the result of people searching for a cultural identity, plus the work of musicians and inventors. Once the first instruments had been produced by their creators, they sparked all sorts of questions. Some were as simple as “how shall we play this?”, and no sooner had one begun to grasp that, “what are we going to play”? These interrogations are at the heart of what is happening now. It so happens that I experienced this period. I also experienced at close hand lever harp teaching in its infancy, as it began to be undertaken in institutions. I was fortunate enough to discuss its potential and its future in the cultural landscape – Breton, first of all, thereafter French. The issue was the place of what was loosely termed “traditional music” in musical teaching centres. It was important to me to document these debates. Now, everything seems settled and established since – as my pupils sometimes say – the dawn of time.

How do you see the lever harp today?

I am amazed to see what has been achieved in less than seventy years. Whether it be in technological terms, in playing techniques or concerning the repertoire, there has been enormous progress. These three elements always advance together, they are inseparable. Regarding the lever harp, the various professionals in each of these fields come together in healthy rivalry, with all their expertise and creativity working to advance our instrument. The number of personalities involved in this process – harp makers, harpists (including concert harpists), composers, teachings – which make the lever harp so vital, is incredible. The energy put into the process is tremendous! It has allowed our little instrument to attain a level of excellence comparable with any other, in under a century.

How do you see music teaching today?

That’s a big question. Rather than thinking of “pedagogy in the music field”, I prefer to think about “teaching music”. First of all, I can see that the standard of music-making is much better today than in other times – so the teaching has got better too. That said, if teaching has changed a lot, it is perhaps because the concept of music itself has changed enormously. The change the has definitely interested me the most is the opening of the doors of the conservatoire. This was an intelligent politico-cultural decision, which finally made music accessible to the greatest number of people. I am sure that we discovered talents in this way, who we were passing by without knowing it. Basically, during the 1960s, music was often a matter of social class. It was almost dynastic: one played the harp as did one’s mother and grandmother, because there was a harp in the house. It was the same for the piano or violin. The other criteria was morphological: you were simply made for it – or you weren’t. The creation of music schools, and the thinking about teaching that was automatically generated by this, are incontestable, major social advances. So, teaching became organised, which was a good thing more than anything else. On the other hand, it was believed necessary to scholarize music. It is a bit of a shame to attempt to solve issues regarding the transmission of art, with the tools of the school of Jules Ferry. I have my reservations concerning a system that, if you are not careful, can be just as exclusive as that of social class. There is no good reason to exclude a motivated, engaged music pupil. The most important thing is to see the ‘music pupil’ as a ‘pupil musician’. It is complicated, like it always is, to reconcile openness and exactitude about quality. You have to reflect and think a lot about it.

Your last recording “Chall ha Dichall” came out in 1998. Haven’t you wanted to record again since then, and deliver your own interpretations?

I have a difficult relationship with recorded music. I much prefer to go to a concert. Recording was once the pinnacle of a career, a sort of field-marshall’s staff. But this meant that one recorded when one couldn’t play any more…as for me, I like to invent, improvise, make contact…be part of a team with my audience. So I am more about movement, rather than the static quality of something engraved on a disc.

As for the second part of your question, I refer to the philosopher P.Ricoeur who said, speaking about books, that “the reader is absent from the writing”. This is what leads the reader to construct a story that is sometimes considerably more different to what was written. It is the same for music. Performance is a type of rewriting – and to know what musicians were going to do with my music was much more interesting for me, than to play it myself. Like all composers, I dream of hearing my music played by others. Also, I am only very rarely satisfied with how I play, so to leave another trace of that is an exhausting thought.

In your CD booklet, you write that the lever harp’s “aptitude for transcending time and musical boundaries has made it an instrument in itself.” It seems that one of your goals was always to bring the lever harp out of its confined identity, from an instrument belonging to one type of music, to become a multi-faceted musical instrument?

Yes, that’s true. For a long time, ever since I began the pedal harp, I was on a sort of quest to give our instrument a multicultural repertoire, and genuine recognition from the establishment. We are not completely there yet, but I’m not losing hope. Isn’t it a fine destiny for an instrument promoted by the Celts, one should even say by the Bretons? The lever harp joined the French baccalaureate syllabuses in 2016. This was an official recognition that the harp is a musical instrument – not an instrument for a particular type of music.

You have also accompanied numerous poets, played a lot with the storyteller Alain Le Goff, and set up a dialogue with Paul Taylor, poet and professor at the University of Rennes, about your research work (a meeting which notably gave rise to the collective publication by nine ‘artist-researchers’ called “Poetry and Music in Education, in a creative perspective”). Is the rapport between words and music, or more broadly the interaction of different art form, important in your eyes?

Absolutely crucial. Words are a type of music. I was lucky enough to meet many wonderful poets. They all said that my music was poetry. I think that what they meant was “music is poetry”, or to put it another way, “to know how to sing is another way to know how to rhyme.” The poets were always surprised to learn that when I play with them, I don’t hear the words they use, but only their rhythm and resonance. It was this that allowed me to accompany them and improvise alongside them. It was a sort of contra-chant. For the stories it was different, more like providing music for film.

I like to speak of complicity even more than a relationship between the arts. Even there, there are some qualifications! It would take too long to go into but I think it is sometimes important to redefine the idea of art, which is not a brief topic. On the other hand I sometimes ask myself if it is not an individual notion, at the end of the day.

How did your collaboration with François Pernel start?

François Pernel participated in an international competition which Jakez François organised in Nantes. François played, for his free choice, a piece by my friend, the sorely-missed Kristen Noguès. I was charmed by the quality of the performance, but also very surprised to hear the work. I knew that it had not been edited at all (Kristen did not want people playing her music). François Pernel had learned it all aurally, from a CD. So it was Kristen and Jakez François who caused me to meet François Pernel.

And how did the idea of making a CD with François happen?

This was François’s idea. At some point, he heard me play in Dinan – I was playing Excalibur, Fantasmagories or St Efflam, I don’t remember exactly. He asked me if I had composed other things. I said that I had lots in my files. This was how the idea was born. François wanted to pay homage to someone he considered to be a fighter for the elver harp. First of all, he wrote a piece he called “Gwerz for Mariannig”, which he played in Dinan, I was very touched. Then he decided that the best way to leave a trace of this pioneering time for the lever harp, would be to record a CD. He chose my work. I felt very honoured and even a little dépassé by how the project unfurled.

How did you realise the project, how did you work together?

First of all, we got to know each other. We began with numerous phone calls. I told him about the beginnings of Telenn Bleimor, on the back of an envelope. Then I described the harmony and composition lessons I took with my masters G. Dandelot and J. Richer. I evoked the hours of writing each evening, after lessons, at the time where lever harp repertoire simply did not exist. There were no photocopiers either, when thirty students enrolled in my lever harp class at the Brest conservatoire. There were plenty of anecdotes! Then he came to my house to explore my archives. He sightread many things – we made music together, in other words. He asked me about interpretation, he played my harp, and got to know me well.

How did you choose the tracks for the disc? Was it difficult?

Difficult is perhaps not the word, let’s call it “delicate”. We took a lot of trouble. I would have liked to have recorded Baleaden an ene (a concert piece for lever harp, cor angles and string orchestra), and some chamber music – I love to mix together sound colours. But it proved complicated to get so many musicians together.

We had first envisaged only featuring music composed in my established style. Finally though, we decided it was important to evoke my roots as well – those also of the lever harp – and to show the two sides of the double culture (Breton, and classical) from which I was lucky enough to come. François practised the pieces and we met regularly to work on them together. I was torn between letting him take over my music, as I so much like to do with my interpreters, and guiding his hands. He wanted me to make my mark on this album too, and give it a historical dimension. I was among the first to compose for the lever harp in a regular manner, and with this language. Incidentally, this is why the first track on the disc is the gwerz Ker Ys, played by me on my harp – and the last track is the same gwerz, performed by François, in his interpretation, on the Excalibur. It is a sort of witness.

How did you choose the recording location? Saint Gildas de Rhuys has a special meaning for you…

St Gildas is the place of my childhood. Practising in the footsteps of Abelard seemed a good omen to me. The stones of the abbey have been echoing for over a thousand years, they are as old as King Brian Boru. I find that the sound engineering – also done by François – and the mixing done by Gurvan L’helgouac’h are a real success, from this point of view. In the album there is a very special sound, of the legendary Norman church of my youth, together with the smell of incense, and the blessed bread that the children of the choir distributed at the end of Mass, when we were young. I thank François for accepting to play in this church, where conditions were very difficult, and the civic authorities of St Gildas who lent us the space. It is not straightforward to work in a historical monument.

I would like to add that Jakez François joined the story very willingly. He has warmly encouraged and supported the project. The harp on which François has recorded the disc is called Excalibur, like one of my most-performed, most-recorded pieces.

What projects do you have coming up? Could you tell us more about “Les Bonheurs de Sophie”, or other future publications?

I continue to write music. I’m working on a project that is mostly (but not only) about gwerz music, with a central theme written by a poet.

I am looking for an editor for “Les bonheurs de Sophie”. It is a very short, illustrated book, to explain the point of solfège to young students. At the beginning of my studies, I was lucky enough to work on oral and written methods, and on the teaching and learning of solfège. “Les bonheurs de Sophie” are the fruit of this research project.

I would also like to publish my book “Et la harpe devint celtique…” (‘And the harp became Celtic…’). This is the result of a different research project, also done at the University of Rennes, but in the department of Breton and Celtic Culture. The book aims to portray the appearance of the lever harp onto the cultural circuit in a new light. It finishes with a gallery of portraits: those who have made our instrument what it is today.