Camac Blog

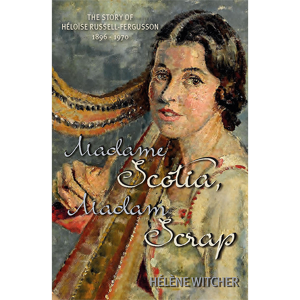

‘Madame Scotia, Madame Scrap’

News

February 1, 2018

Hélène Witcher has published a life of her aunt, Héloïse Russell Fergusson: ‘Madame Scotia, Madame Scrap’ (The Islands Book Trust, 2017). Russell Fergusson (1896-1970) was a fêted exponent of the Scottish Clarsach during the first Celtic Revival, at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Her onstage persona was of a romanticised Celt, dressed in flowing white robes, singing Hebridean songs and accompanying herself on the harp. She won considerable acclaim for this – including being made a Druidic Bardess at François Jaffrennou‘s Celtic Congress in Brittany.

Hélène Witcher has published a life of her aunt, Héloïse Russell Fergusson: ‘Madame Scotia, Madame Scrap’ (The Islands Book Trust, 2017). Russell Fergusson (1896-1970) was a fêted exponent of the Scottish Clarsach during the first Celtic Revival, at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Her onstage persona was of a romanticised Celt, dressed in flowing white robes, singing Hebridean songs and accompanying herself on the harp. She won considerable acclaim for this – including being made a Druidic Bardess at François Jaffrennou‘s Celtic Congress in Brittany.

Druidic credentials notwithstanding, Russell Fergusson discovered the Celtic harp in a storefront window in downtown Washington DC, where she was employed as a piano teacher following classical studies at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Scottish though she was, she was hardly born a Celt – her parents were non-Gaelic speaking, urban Glaswegian bourgeoisie, and her exposure to Gaelic as a small child came from the family’s nanny and housemaid. Nonetheless, she felt immediately drawn to the small harp, decorated with Celtic symbols:

“I was swept thousands of miles back to where the seabirds shrilled above the gale as they did centuries ago. The Hebridean people’s songs! I lost all sense of time. I was spinning with them; milking. I was waulking the cloth although I HAD NEVER SEEN THIS DONE. I keened tragically on the shore with the rest when the lads failed to return. That had happened so often. I was quite, quite familiar with these islands although I HAD NEVER BEEN THERE!” (p. 40).

From the Camac collection of historical harps: Irish harp ‘junior model’, n° 645 jr (Syracuse, New York, 1920-1930).

This imaginative reaction is typical of the first Celtic revival. The revivalists were mostly middle-class intellectuals – some political reactionaries, others romantically-inclined spiritualists like the devout Christan Scientist Russell-Fergusson. In any case, they were untroubled by contemporary notions of historical accuracy. It was the Breton-Parisian Théodore de la Villemarqué, researching oral Breton literature, who found the harp mentioned. He optimistically concluded that the harp had belonged to Ancient Breton bards; even to priests. Unsurprisingly (for writing was especially forbidden in Celtic religion), no document told him this. There is also no one definitive type of Celtic harp, and revival harps were built and part-invented by the harp makers of the time (one of Russell-Fergusson’s harps bears the affectionate inscription “this clarsach, the first of its kind, was made in Haslemere in July 1932 for Heloise Russell-Fergusson by Arnold Dolmetsch”). Russell-Fergusson was not a historical performance practitioner. She remained active as a classical pianist, as well as giving concerts of Hebridean songs with her Syracuse harp (presumably a Clark – we have a similar one in the Camac collection). She also gave several recitals together with concert harpists, such as Mildred Dilling and Maria Korchinska.

Despite this interpretative melting-pot, it is interesting to note that in later life Russell-Fergusson took great pains to tape-record her songs, and the sound of the Scottish sea, seagulls and the wind. What the revivalists all had in common, was a yearning for a satisfactory cultural narrative – one usually different to the one they had grown up with. Often figured as a Romantic return to the power of nature in an otherwise modern, industrial age, they also sought to preserve their stories for others.

Today, a romanticised view of Celtic cultures has become almost as unfashionable as Christian Science. Even in Russell-Fergusson’s heyday, it was questioned by plenty of critics. But for any musician interested in the lessons of history, it is as important to study unfashionable ideas, as any that are currently rated. If you don’t interrogate your perspectives, particularly by comparing them to those of others, you are not thinking critically, and it is difficult to develop as an artist. The more you examine musical and cultural thought over time, the clearer it becomes that notions of authenticity are fluid – and, for this fluidity, no less sincere. The Celtic revival captured the imagination of many, and still does today in its contemporary forms. Modern traditional music is one of the most open musical forms in existence, easily fusing Celtic roots, jazz, rock, the avant-garde. By the satisfaction and the joy everyone derives from it, many of us with a classical music background can reflect that something does not have to be absolute in order to have meaning or value.