Camac Blog

Freedom and fulfilment: the art of orchestral freelancing

News

February 3, 2020

Germany, land of music, is home to the world’s largest number of secure orchestral jobs, and probably some of the best working conditions for musicians. But even in Germany, statistics from the labour market make sober reading. Die Zeit Campus recently reported that across all instruments put together, there are 9746 orchestral positions in Germany. These produce between 120 and 160 vacancies a year, plus about another 300 temporary contracts and academy places.

Photo: Manuel Nägeli

For these few hundred jobs, 800 musicians graduate yearly from Germany’s conservatoires. As you don’t always win the first audition you go for, the German Orchestral Association reckons that on average, 4 years’ worth of graduates are applying at the same time. That’s about 2400 musicians trained in Germany, applying for about 140 jobs. They are joined by further applicants from abroad.

Despite the pressure, it wouldn’t arise if being a musician wasn’t – fundamentally – an amazing way to make a living. There are lots of distinctly un-amazing things musicians do to make a living, but no profession is all glamour. Students are not flocking to colleges all over the world because their parents are saying what a great idea; they go because music is full of wonder and joy. It’s lucky for civilisation that it is not easy to convince eighteen-year-old human beings to pursue less beautiful paths, once they have one in their vision.

Conservatoires who prepare their students effectively for an increasingly freelance profession do not waste much time bemoaning the lack of jobs. It is much more constructive to be taught that you need to get good at freelancing. If you are, you’ll find much to love about your life in music.

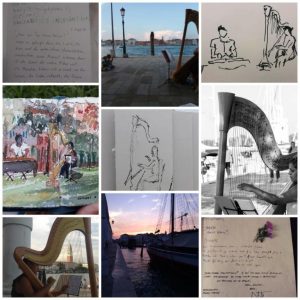

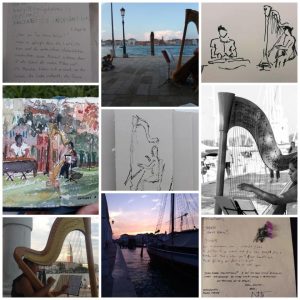

Nabila Chajai is living proof that freelance careers – including those with strongly orchestral points of focus – exist at the highest level. She is a graduate of France’s two biggest schools: she studied in Isabelle Moretti’s class at the CNSMDP, followed by a Masters in Lyon with Fabrice Pierre. She is a prizewinner of distinguished competitions, for example the ARD in Munich, the Martine Géliot competition, and the Marcel Tournier competition. Her professional career includes the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Claudio Abbado’s Orchestra Mozart, the Berlin Philharmonic, Orchestre philharmonique de Radio France, Orchestre National de France, Orchestre philharmonique de Strasbourg, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the RAI National Symphony Orchestra in Turin, the Orquesta Sinfónica de Bilbao, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and the Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia. For the last few years, she has been working at one of the world’s most famous opera houses: the Gran Teatro La Fenice. Summer visitors are delighted by the musical postcards she performs all around the city, during the orchestral recess.

“It’s important to remember”, says Nabila, “that the competition is just really high everywhere, and that’s no reflection on your own abilities as a musician. Every audition, competition and job you do has the potential to lead to further work. At one audition I did, I did not win the job but a member of the jury recommended me for the Orchestra Mozart. Once there, Abbado liked my work and invited me to come to Lucerne, and to the Mahler Chamber Orchestra. This opened the door to getting called by the international ensembles.

It’s exciting to work in so many different places, and to get called for difficult work. Interestingly, I’ve met a lot of musicians in jobs we all think we’d love to have, who are not happy in their work. They get bored, stop practising…lose themselves somewhere along the way. Strangely, I’ve found the most contented colleagues in the Netherlands and the UK, where conditions are among the toughest and least well-paid. Maybe it’s because they have more choice; the freelance scenes in these countries are highly-developed, and some people choose to leave orchestral jobs. They’ve learnt not to fear the insecurity, because if you’re good and well-networked, your phone is going to ring. If you’re not tied to a busy plan of services, you can choose more high-end work, not less.

I’m happy to communicate my experience, because young musicians need to be prepared for the profession as it evolves. The more ready you are to think flexibly, and spot advantages in new or unexpected situations, the better. Successful musicians have always done this. They create their own opportunities.”