Camac Blog

Demystifying new music: Marcos Balter, Parker Ramsay and “Omolu”

Latest

July 7, 2021

Mission: Commission is a fantastic initiative from the Miller Theater at Columbia University, NYC. It not only commissions new classical music, but communicates and demystifies the composition process: their excellent podcasts feature both composer and artist, discussing their collaboration. Excitingly, the harp is the focus of one of the three pairings, as Parker Ramsay premiers Marcos Balter’s “Omolu”.

We are also lucky enough to have a blog written by Parker about the project! How did his Canopée harp came to be tied up with shoelaces? Read on…

We are also lucky enough to have a blog written by Parker about the project! How did his Canopée harp came to be tied up with shoelaces? Read on…***

“Chance encounters can lead to unexpected journeys. I bumped into Marcos Balter on Upper West Side of Manhattan in late 2019, which we followed up with a coffee shortly before the March 2020 lockdown. Before long, a harpist and a composer were in cahoots. Marcos is a superstar, commissioned again and again to write for some of the world’s most eminent soloists, orchestras and ensembles. In sitting with him, my sense of potential intimidation put to rest by his bubbly personality and the excitement when he asked me point blank “what are you looking for in a work for solo harp?” Not knowing exactly what the appropriate response should be, I responded with “something hard.”

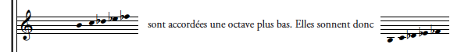

Fast forward to early 2021, and Marcos and I were meeting on Zoom to discuss extended techniques and toys such as screwdrivers, water glasses, spatulas – all the “stuff” that we harpists tend to associate with new music. We were working fast, as six weeks to collaborate on a new piece for the Miller Theatre at Columbia University. Marcos’ writing process was all documented in Mission: Commission, a podcast which traced the workings of three composers as they created a new work for a soloist in a short period of time. But after a while, he eventually decided to dispense with toys and auxiliary tools. Instead of having me change my technique, he had me change the harp itself. Indeed, two weeks before recording day, I was handed a work in scordatura, reducing 10 strings normally spanning an octave and a third down to a minor third in microtonal increments.

The mind goes two places in situations like these. First there’s there “wow!” moment, followed shortly by, “how on earth am I going to pull this off?”

While I had encountered scordatura at the octave in George Apheghis’ Fidelité, I had yet to come across a work which required the density of scordatura as in Omolu.

As with much new music, there is no guidebook for what to do. You have to use empirical methods to figure out how to get the harp to the score’s appointed destination.

As I brought down the pitch of the strings that far, several problems arose because of the extreme reduction in tension. First, the projection was lost. Secondly, the tuning was not reliable (a big problem when the work is reliant microtonality). And lastly, when changing pedals, the gears were pressing too far into the strings, altering the pitch of strings by as much as a whole tone or more, rather than just a semitone. It was clear I was going to have to change out some strings.

Of course, with modern harps, we’re used to something a little more straightforward. Strings come in packages with labels, and we know that the 3rd octave C is 3rd octave C. it may differ in material, or ever so slightly in width depending on the manufacturer, but there’s a degree of systemization and consistency that means we often don’t have to think about. And such is to our benefit, as two centuries of accumulated wisdom in harp manufacturing since the industrial revolution has rendered the production of large and reliable instruments that can hold up on the orchestra stage.

The point of reference for addressing the issue, however, came from glancing over at my baroque harp in the corner. If gigging on the historical performance scene has taught me anything, it is that the materials you put on your instrument and the pitch of your instrument are interrelated and can fluctuate depending on the gig, the rep or the weather. Gambists and lutenists are constantly playing with gauging and string material, trying new things out to see how they can best get the instrument to resonate. A couple of years ago, I ended up increasing the gauging on my baroque harp, as I found myself playing at A392-415 more often than A440, thus requiring that the strings be more taut to achieve the same level of projection in a place as humid as Manhattan.

In the end, I took 4th and 5th octave strings and placing them where 3rd octave strings might normally dwell. I would have done it with ALL 5th octave strings, but the holes in the tuning pins are graduated in accordance with the normal string gauging. (In future, it is my hope to have time to acquire extra pins and change them out to get some more consistency in tension). After a day or so of experimenting, I found a result I was happy with (but though of course, I was now left with a harp with the sole ability to perform a new work by Marcos Balter).

| String | Gauge | Pitch |

| 4th Oct A | 146 mm | A♭3 (207.7hz) |

| 4th Oct B | 140 mm | B♭3 (233hz) |

| 4th Oct C | 130 mm | C♭3 (246.9hz) |

| 4th Oct D | 187 mm | A 3 (213.7hz) |

| 4th Oct E | 177 mm | B 3 (239.9hz) |

| 3rd Oct F | 168 mm | B 3 (254.2hz) |

| 3rd Oct G | 159 mm | A♮ 3 (220hz) |

| 3rd Oct A | 146 mm | A 3 (226.5hz) |

| 3rd Oct B | 140 mm | C♮ 3 (261.6hz) |

| 3rd Oct C | 140 mm | C 3 (269.2hz) |

Beyond the scordatura, there is another element in Omolu that required some thinking about. Marcos was keen for an extended passage using multiphonics on the bass wires. Of course, there are ways to engage multiphonics with the hands, such as memorizing an appropriate place on a string, engaging the harmonic and plucking the string with either the fingertip or even the fingernail. The result is adequate, but not great for if you want a bit of virtuosity.

As such, the question of how to prepare the strings properly came about. After some experimenting, it was apparent that an even surface around the string was the most reliable means of muting the fundamental pitch while accentuating the upper frequencies in the harmonic. I tried using everything from placing cat toys in between strings (which produced thudding effects) to placing hairclips on the strings (which produced a very metallic attack, but not much resonance), until I realized that the essential problem boiled down once again to a matter of tension.

Thus in order to create the necessary tension (balanced with the desire for an even surface around the string), I tied wax shoelaces once around the strings and around the column of the harp. The resulting clarity of the harmonics was satisfactory (I intend to keep experimenting with other types of shoelaces), but what was really fun was getting to see how pitch of the multiphonics could be bent by manipulating the tension of the shoelace backwards and forwards, resulting in portamento/glissando effect.

Omolu is still growing under my fingers and in my ears, and I intend to keep experimenting over the next year to see how far I can go in preparing the strings on my Canopée to tap into the sound worlds of a harp which lay behind the veil of our own conventional training. One might think of this as an essential part of Omolu, named for one of the more popular deities in African diasporic religion known as Orixás. In Brazilian Candomblé, Omolu is the deity associated particularly with epidemics, being syncretized with the figure of St. Lazarus. Bearing a face so scarred by disease, he cannot be looked upon and appears in ceremonies and with a raffia masquerade covering his whole body. To me, Omolu is a fascinating figure, as his divinity, invisibility, untouchability all emanate from diseases that you or I could fall prey to, same as anyone else. It is sickness, not health, that is the source of his transcendence.

And likewise, the harp’s internal “disfigurement” (for lack of a better term) is what helps tap into something other-worldly. Talk to many composers, and the first thing they’ll say is “I can’t get my head around the harp.” The instrument is intimidating and its limitations at first glance render it difficult to deal with. But the really great composers for the harp are those which see its “setbacks” as an opportunity, trying things that I would not think of doing myself for no other reason than that I am too close to my instrument. Our technical training as harpists is long and intense but can come with a tradeoff: we might not know what we’re missing about our instrument’s potential until we bring others along for the ride.”

Parker Ramsay

Fascinating and original!