Camac Blog

Clarsach for Communities

News

January 29, 2018

Among the many, important musical outreach programmes which do so much good today, particularly praiseworthy (if particularly difficult to get off the ground) are the extended projects, which supply lessons and instruments to the same group of children over a longer period of time. We’re delighted to be supporting Ailie Robertson‘s Clarsach for Communities. Held in the Muirhouse district of Edinburgh, this is an intensive clarsach tuition programme for primary-school-age children, using a variety of immersive music teaching methods delivered after school and during the holidays. There is no charge for the tuition, instruments, healthy snacks, and performances.

Among the many, important musical outreach programmes which do so much good today, particularly praiseworthy (if particularly difficult to get off the ground) are the extended projects, which supply lessons and instruments to the same group of children over a longer period of time. We’re delighted to be supporting Ailie Robertson‘s Clarsach for Communities. Held in the Muirhouse district of Edinburgh, this is an intensive clarsach tuition programme for primary-school-age children, using a variety of immersive music teaching methods delivered after school and during the holidays. There is no charge for the tuition, instruments, healthy snacks, and performances.

“I had the idea while I was doing my PHD, which is about composition, but contains a lot of social-political research”, Ailie explains. “I also used to often work for Edinburgh council, so I experienced the effects of austerity measures at first hand. There are hardly any funded peripatetic music lessons in Scotland any more – every council has their own policy, but generally it’s one of the first things that gets cut.

I also thought that because the clarsach is such a big part of Scottish cultural identity, it would be a great point of integration for children who have arrived in Scotland from other cultures.

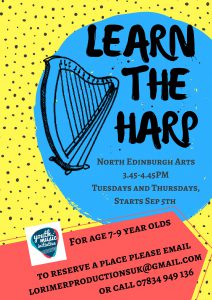

We received funding from the Youth Music Initiative and North Edinburgh Arts to run one group of twelve children aged between seven and nine. They have two lessons a week, and fifty percent of this is musical games, Kodály and so on for their whole musicianship, the other half is clarsach teaching. We deliberately have a mix of kids from different schools, so they build a new community with each other. We also discovered that all the boys are happy to join in, because they have no preconceptions about the harp. We’re looking forward to our first Christmas concert on December 22nd!

While the most obvious triumphs of ‘Clarsach for Communities’ are musical, the real impact is behind the music. These young people learn confidence, resilience, ambition, and a multitude of transferable skills to support them across all areas of their lives. The ultimate goal is to boost educational performance, health and wellbeing so that children grow to achieve their full potential, contributing to positive communities.”

Music is often described as middle-class, but actually, it’s not true. One remarkable characteristic of the musician community is that it doesn’t define itself by class at all. Musicians are brought together by music. This is even the case in England, where your social standing can otherwise be judged by what you eat in the evening, what time you consume it and indeed whether you call the meal supper, dinner or tea. Music stands above all this, and a great relief it is too.

Music lessons, however, do become middle-class. They cost money and so do the instruments. If they are not publicly funded, they forcibly become impossible for those who cannot pay – and this exclusivity is much more destructive than is commonly recognised. If music lessons are middle-class, most people assume, logically enough, that music is too. You will see it as a necessary, or an unnecessary, accomplishment or appendage for your child. The class-ification of music reduces it to an accessory, and this is what is damaging. Perceive it as an accessory, and there is no more argument to fund it for society.

Moreover, with bleak irony, it is precisely disadvantaged groups of children who stand to benefit most from what music lessons can offer. Another extended project we have sponsored is with DEMOS (Dispositif d’Education Musicale et Orchestrale à vocation Sociale), in the Barbès district of Paris. The children received three hours of classes a week over more than two years, as well as the crowning glory of participating in orchestral performances. Delphine Benhamou taught the harp section, and observed the following:

“If you are a child your teachers have decided is a weak or difficult pupil, or you are generally in a weak or difficult school, your confidence is very low. You’re afraid to be seen to try things in case you fail, you’re afraid to admit you care about the outcome, and you have no sense of your own value or place in the world, because nobody has ever told you you have some. All the classes I ran for DEMOS were group lessons – along with two other professors, I taught a mixed group of clarinet and harp. The first thing we had to do was boost the group’s confidence. We were accompanied by a very helpful team of social educators, who took part in the lessons alongside the children. For example, the director of the local leisure centre learnt the clarinet. This allowed the children to feel on a more equal footing with adults, learning together instead of always being the ones who were stupid or naughty. Three hours a week is also a lot of lesson time, and apart from anything else, it’s often your time that children need most of all. “Quality time” is a phrase dreamt up to make adults who don’t give their children a lot of time feel better. You can’t win someone’s confidence like a fast washing-machine cycle.

More confidence makes you more prepared to work at things where you are not guaranteed definite or immediate success. The workshops taught the children that if they worked at something consistently over a long period of time, they could arrive at something they could be really proud of. At the end of the project, we had a school fête where the parents came, brought food they had cooked, and the children performed in the orchestra. The children were able to see they had learnt to do something that made their parents proud of them.

Another important, deliberate aspect was that all the work be collective. In the group, and ultimately in the orchestra, the children learn that they have an individual role to play that is important to the success of the whole. I don’t think it’s too grand to say it gives them a sense of place and value in the universe.

The music lessons also provided them with a way to see and appreciate talent that don’t have a chance to surface at school or in their day-to-day lives. One of the children in my class was autistic, and couldn’t speak at all. But he could repeat whatever I played on the harp, including two hands playing different lines, after one hearing. The children saw him in a new light – suddenly, he was the talented one, and he became respected and admired by the rest of the group.

Also, the harp was special. In a survey run by DEMOS at the beginning about which instrument the children would most like to learn, in their dreams, the harp came out on top. In Barbès there are a lot of children of African origin, and when I travelled myself to Africa, I was told that the harp, the African kora, is a sacred instrument. Symbolically, it’s the link between earth and sky. I don’t know if that has anything to do with it. But certainly many people, of whatever culture, find the harp to be profoundly touching in some way. The children always approached their harps very carefully, even with reverence, and there were often moments of real stillness and concentration during the lessons I will never forget.”