Camac Blog

Le Tombeau de Debussy: repertoire for flute, viola and harp

Latest

June 16, 2019

The Camac blog is unlikely to disapprove of music written for or with instrument makers – and in any case, this type of collaboration has always played a part in musical development. The better an instrument is, the better the artist who will be interested in playing it, and the better a composer who’ll be inspired to write music for them. Great artists playing fine music inspire the luthiers further to improve their instruments, in a positive cycle. For a well-documented hotspot of such activity, look no further than the harp, fashionably late to the nineteenth-century party of extended chromatic richness. The Debussy Dances were commissioned by Pleyel to show off their chromatic, cross-strung instrument; in competition, Érard asked Ravel to write the Introduction et Allegro for the double-action harp. Commercial and artistic growth are not mutually exclusive, and it’s unrealistic (and a bit reductive) to claim they should be.

That said: the Debussy sonata for flute, viola and harp L. 137 wasn’t commissioned by a luthier, and hasn’t got virtuoso instrumental display on its agenda. It was not commissioned at all, but rather was part of Debussy’s late series of six sonatas for various instrumental combinations, inspired by the French baroque clavecin. As Debussy emerged from his creative paralysis of 1914, his music became pared-down, meticulous; a harbinger of the Neoclassicism / absolute music of the interwar period. Debussy never liked the term Impressionism (calling those who used it “imbeciles…particularly…the critics.”). Whatever you think “impressionist” means, the trio sonata bears little evidence of the composer’s earlier lush textures, infused with the exotic lights and sounds that had so delighted him at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889.

That said: the Debussy sonata for flute, viola and harp L. 137 wasn’t commissioned by a luthier, and hasn’t got virtuoso instrumental display on its agenda. It was not commissioned at all, but rather was part of Debussy’s late series of six sonatas for various instrumental combinations, inspired by the French baroque clavecin. As Debussy emerged from his creative paralysis of 1914, his music became pared-down, meticulous; a harbinger of the Neoclassicism / absolute music of the interwar period. Debussy never liked the term Impressionism (calling those who used it “imbeciles…particularly…the critics.”). Whatever you think “impressionist” means, the trio sonata bears little evidence of the composer’s earlier lush textures, infused with the exotic lights and sounds that had so delighted him at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889.

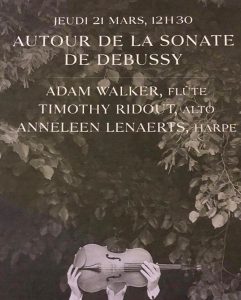

The Debussy sonata, fin-de-siècle masterpiece, invites thought-provoking co-programming of deeper thematic discourse than an intriguing combination of instruments. We were happy recently to send a harp for Anneleen Lenaerts for one such concert with Adam Walker (flute) and Timothy Ridout (viola), at the Auditorium du Louvre on March 21st. This programme also featured Arnold Bax’s Elegaic Trio. It seems eerily impossible that Bax could have heard Debussy’s trio before writing his own, so close together are the dates. More eerily still, the Elegaic Trio is also a response to political disaster: Bax’s sad homage to friends killed or imprisoned in the Irish Easter Rising of 1916. We also heard Salzedo’s transcription of Ravel’s Sonatine pour piano (1903 – 1905): another neo-classical evocation of the grace and purity of the Antique world (particularly in the second mouvement de menuet).

The Debussy sonata, fin-de-siècle masterpiece, invites thought-provoking co-programming of deeper thematic discourse than an intriguing combination of instruments. We were happy recently to send a harp for Anneleen Lenaerts for one such concert with Adam Walker (flute) and Timothy Ridout (viola), at the Auditorium du Louvre on March 21st. This programme also featured Arnold Bax’s Elegaic Trio. It seems eerily impossible that Bax could have heard Debussy’s trio before writing his own, so close together are the dates. More eerily still, the Elegaic Trio is also a response to political disaster: Bax’s sad homage to friends killed or imprisoned in the Irish Easter Rising of 1916. We also heard Salzedo’s transcription of Ravel’s Sonatine pour piano (1903 – 1905): another neo-classical evocation of the grace and purity of the Antique world (particularly in the second mouvement de menuet).

Toru Takemitsu’s And Then I Knew ‘Twas Wind projects us into 1992, but only chronologically. It’s another homage, this time to the Debussy sonata directly: “I am self-taught”, Takemitsu once said, “but Debussy is my true teacher.” The trio both depicts the wind, and via this also a sense of something more spiritual. So too can you read Emily Dickinson’s ‘Like Rain It Sounded Till It Curved’, from which Takemitsu takes his title.

If this isn’t enough to inspire your Debussy trio programming, Gérard Chenuet – husband of Véronique Chenuet – has made many fine arrangements for his wife’s fl-vla-hp “Trio Mélusine“. These are all also from composers writing around the dawn of the twentieth century, and as such provide a lot of material for your trenchant windows on a complex age. Technically, they’re also more accessible than the Bax or Takemitsu. You can add Brazilian and Spanish flair with works by Ernesto Nazareth, and Manuel de Falla: Debussy was also keenly interested in Spanish music, as evidenced in the Serenade interrompue, Estampes or Images.

You can also touch on the flourishing musical atmosphere of pre-war Vienna, with Chenuet’s transcriptions of Alexander Zemlinksy. “Käferlied” (Song of the Beetle), from Fantasien über Gedichte von Richard Dehmel Op. 9, is strongly reminiscent of Brahms, while “Der Wasserman” from the Vier Balladen is an early work after a poem by Justinus Kerner. Both Paris and Vienna had, particularly in the face of the times, to contend with the death of Romanticism: what happened in the two musical centres was very different.

You can also touch on the flourishing musical atmosphere of pre-war Vienna, with Chenuet’s transcriptions of Alexander Zemlinksy. “Käferlied” (Song of the Beetle), from Fantasien über Gedichte von Richard Dehmel Op. 9, is strongly reminiscent of Brahms, while “Der Wasserman” from the Vier Balladen is an early work after a poem by Justinus Kerner. Both Paris and Vienna had, particularly in the face of the times, to contend with the death of Romanticism: what happened in the two musical centres was very different.

If after all this, your audience could also do with something different: Chenuet has also given some attention to the music of Frank Bridge (1879 – 1941), and Mel (Mélanie) Bonis (1858 – 1937). The Bridge transcriptions focus on various depictions of female figures: Rosemary and Columbine from Three Pieces, Nicolette from Vignettes de Marseille no. 2, and Princess from the Fairy Tale Suite. Mel Bonis drew much inspiration from heroic women of legend: Desdemona, Phoebe, Viviane for example. Chenuet has also arranged the light-hearted Valses-Caprices, and Le Moustique (the mosquito).